Wok-it science

Two cookbooks offer delicious lessons in the science of cooking

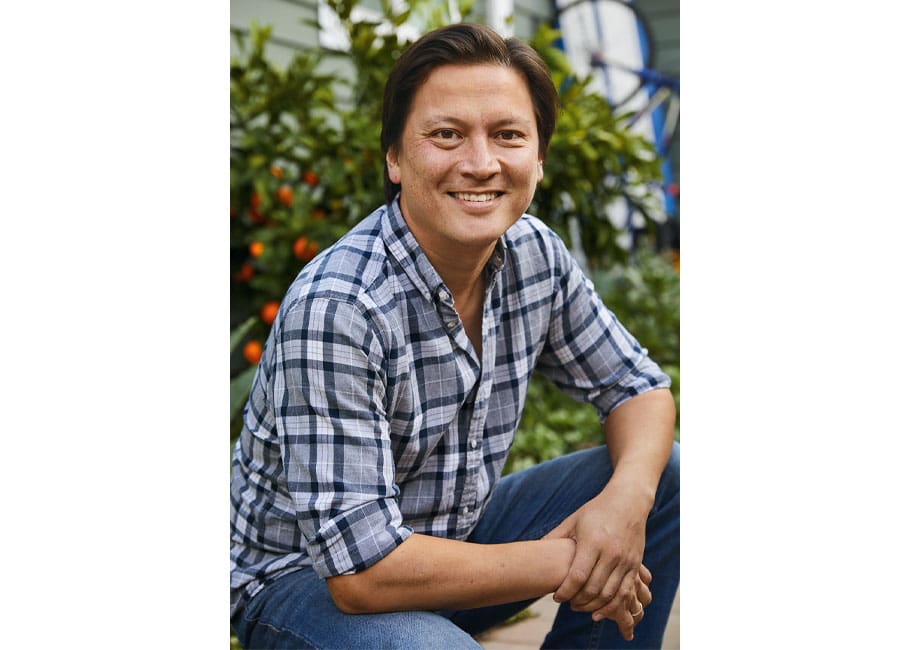

When J. Kenji López-Alt bought his first wok for $30, he never imagined he would be using the same one 20 years later while writing a book about wok cooking. Then again, the New York Times food columnist, restaurateur and Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate has surprised himself on more than one occasion. Like when he left behind his dream of being a researcher with a doctorate in biology and instead got a job in a restaurant kitchen while in his sophomore year of college. “I loved being brought into a new world that I had never seen before,” Costco member López-Alt tells the Connection from his home in Seattle.

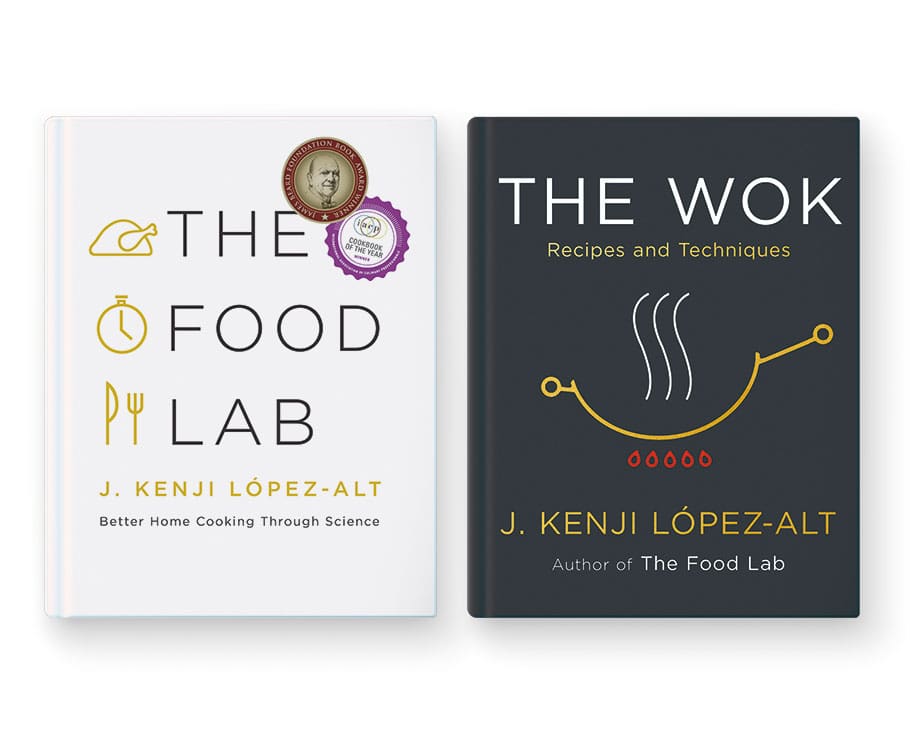

One thing he never relinquished was his penchant for scientific discovery. “I always want to know how and why something works, whether it’s food or a mechanical process,” he says. His first book, The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science, combines his love of cooking and love of science. It’s a brick of a book, full of lab-tested instruction on things like how to make an amazing grilled cheese sandwich (toast the bread first!) as well as tips, recipes and plenty of “experiments” to try (like using whole versus ground spices).

López-Alt intended to have a chapter with wok recipes in The Food Lab, but he ran out of room. He figured he would include it in the sequel, along with a hodgepodge of other techniques and recipes. But once he started writing, he realized he couldn’t possibly contain everything he wanted to say about woks in one measly chapter. So, the chapter became a book: The Wok: Recipes and Techniques.

“There are a lot of great wok cookbooks and history books, but I wanted to come at it from a unique perspective, with science and techniques,” he says. The idea behind The Wok is that once you master a few basic principles, you can make a whole range of dishes with a wok. While a wok is ideal for stir-frying, you can do far more with it than most people realize. “The real thing that makes a wok so useful is its versatility: You can braise, steam, shallow-fry, pan-fry, cook rice and noodles, and so much more,” López-Alt says.

Forget what you think you know about woks first, though, because you’re probably imagining specific restaurant-style wok cooking, which requires a special burner and extremely high heat. López-Alt recommends a 14-inch, flat-bottomed wok that sits on a Western-style burner and requires nothing special to function. “For about $40, you can have a great pan,” he says.

And with it, a host of great meals.

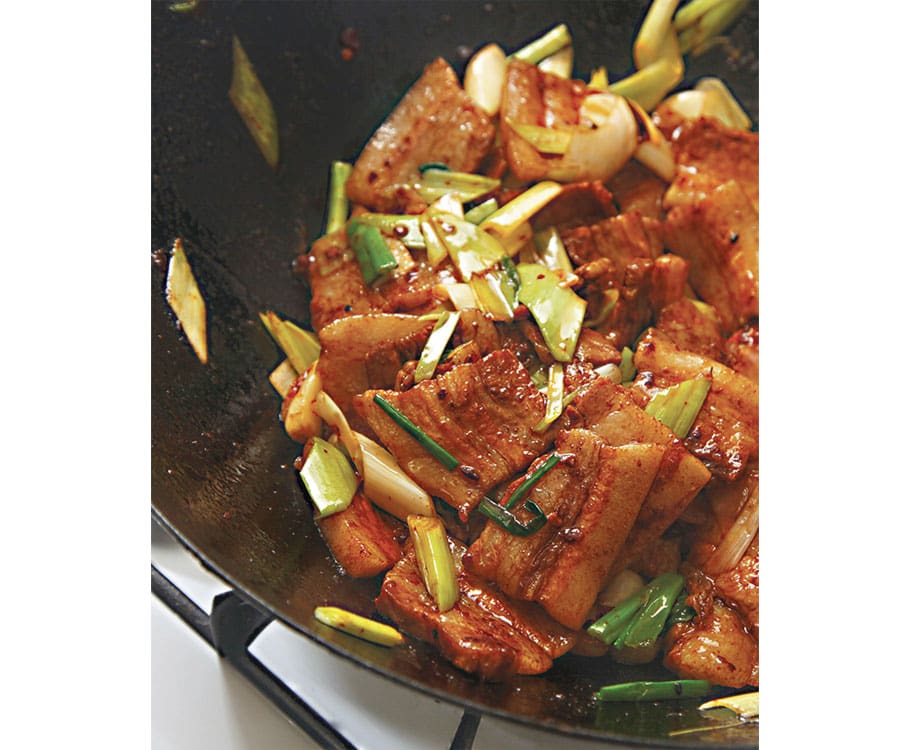

I tested this side by side with two batches of sliced pork. The first I washed thoroughly in cold water before squeezing dry in a fine-mesh strainer and stirring with a basic marinade. The second I sliced and immediately stirred with the marinade. There was an immediate visual difference between the two batches: The washed pork had a distinctly paler color.

After letting both batches rest for half an hour, I stir-fried them and tasted them side by side. The differences were subtle but noticeable. The pork that had been washed vigorously had a more tender, almost slippery texture (a good quality in most stir-fried meats) and was more thoroughly seasoned—the mechanical action of washing and squeezing loosens up the muscle fibers of the meat, improving their ability to absorb and retain marinade. Given it’s such an easy process, I’ve taken to doing it for all my stir-fries.

Reprinted with permission from The Wok

Stir-Fry Sichuan Double-Cooked Pork Belly

Stir-frying prepared meat

Stir-frying chicken